In post-war Japan, rebuilding quickly meant embracing new technologies. Every decade brought more advancements and a deeper integration of burgeoning computer power. The high-tech future, always a part of Japanese popular imagination, became a source for hope, international competition, and national pride for a people still under the thumb of Western powers. In the 1980s Japan experience a bubble economy whose crash resulted in a deep sense of unease and a disaffection with technology’s promises. After all, technology brought the atomic bomb and the rise of robotics displaced throngs of Japanese workers. Artists began to reflect on what this might mean for a hyper-connected, de-personalized society. Tokyo, the world’s first mega-city, became the setting for dystopian animated movies like 1988’s Akira, and manga (Japanese comics) embraced the grime of cyberpunk and drifted further into existential questions about humanity’s future.

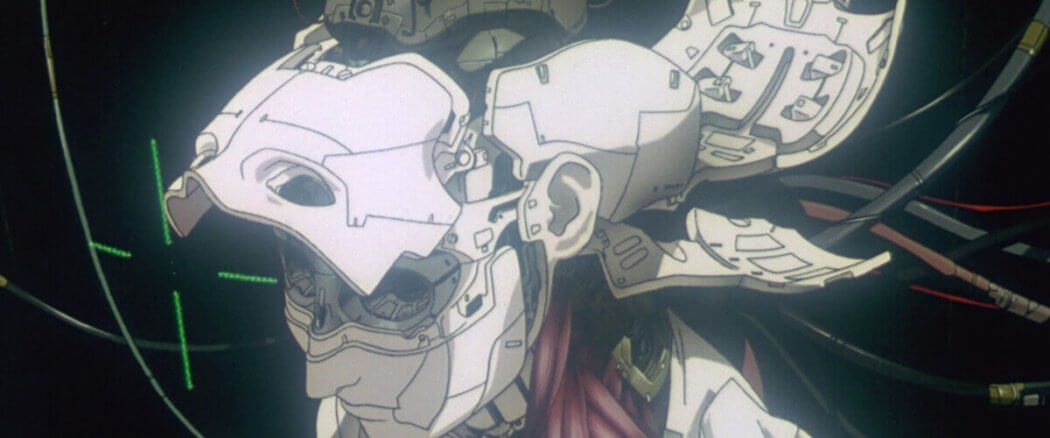

In 1995 Mamoru Oshii debuted Ghost in the Shell, a “cartoon” masterpiece that set the standard for what adult animation can be. It influenced many subsequent Hollywood films, most notably The Matrix trilogy. Beyond the visual beauty lies a story about the near future where hackable, always online wearables (in this case cyber augmentation from brain implants to enhanced eyes to replacement bodies) are forcing users to rethink consciousness and what it means to be human. The “shell” in question is the cybernetic body of Major Motoko Kusanagi, an elite government agent who is almost entirely artificial, possessing only the barest humanity in the form of organic brain matter. “Maybe I died a long time ago…Maybe there never was a real me in the first place,” Kusanagi wonders. She and her team are hunting the Puppet Master who is hacking into cyborgs all across the city for an unknown reason. The twists and turns don’t always make sense, but the common thread throughout is the Major’s angst over what she is.

In 1995 Mamoru Oshii debuted Ghost in the Shell, a “cartoon” masterpiece that set the standard for what adult animation can be. It influenced many subsequent Hollywood films, most notably The Matrix trilogy. Beyond the visual beauty lies a story about the near future where hackable, always online wearables (in this case cyber augmentation from brain implants to enhanced eyes to replacement bodies) are forcing users to rethink consciousness and what it means to be human. The “shell” in question is the cybernetic body of Major Motoko Kusanagi, an elite government agent who is almost entirely artificial, possessing only the barest humanity in the form of organic brain matter. “Maybe I died a long time ago…Maybe there never was a real me in the first place,” Kusanagi wonders. She and her team are hunting the Puppet Master who is hacking into cyborgs all across the city for an unknown reason. The twists and turns don’t always make sense, but the common thread throughout is the Major’s angst over what she is.

Sex and the Cyborg

Much has been made of the fact that the Major often strips down to a “skin suit” during fight scenes. (The skin allows her to become invisible, but also there are nipples on it.) Physical bodies are an important part of Ghost in the Shell: the Puppet Master doesn’t appear to have one, people who have been hacked can no longer trust their bodies (or minds), and Kusanagi is constantly haunted by the “ghost” in her own robotic body that whispers of a humanity that is hard to remember. Her nakedness is post-sexual (like a department store mannequin she doesn’t have sexual organs) and suggests a post-human body capable of inhuman strength, speed, and thought but incapable of creating life. Reproduction has been replaced with replication. There is a male gaze upon her, but none of the male characters view her as a potential sex partner. Director Oshii specifically wanted the Major to be an unsexualized female. For 90s Japan her character represents a breaking down of gender roles and expectations. Though we may see her naked body as possessing a sexuality, she is intentionally never animated as “sexy.”

Much has been made of the fact that the Major often strips down to a “skin suit” during fight scenes. (The skin allows her to become invisible, but also there are nipples on it.) Physical bodies are an important part of Ghost in the Shell: the Puppet Master doesn’t appear to have one, people who have been hacked can no longer trust their bodies (or minds), and Kusanagi is constantly haunted by the “ghost” in her own robotic body that whispers of a humanity that is hard to remember. Her nakedness is post-sexual (like a department store mannequin she doesn’t have sexual organs) and suggests a post-human body capable of inhuman strength, speed, and thought but incapable of creating life. Reproduction has been replaced with replication. There is a male gaze upon her, but none of the male characters view her as a potential sex partner. Director Oshii specifically wanted the Major to be an unsexualized female. For 90s Japan her character represents a breaking down of gender roles and expectations. Though we may see her naked body as possessing a sexuality, she is intentionally never animated as “sexy.”

The Puppet Master, a disembodied intelligence, is also asexual. His (I use the male pronoun because his voice is male) realization that reproduction is one human experience closed to him (the other is death) sets the stage for the climax of the film: he proposes to merge “ghosts” with Kusanagi in a form of virtual, asexual procreation. “A god descends for a wedding,” the lyrics to the haunting opening theme from composer Kenji Kawai state, and their ultimate union creates, not genetic offspring, but remixed code that represents a new form of transhuman life.

Through a Mirror, Dimly

One conversation between Kusanagi and her teammate Batou references 1 Corinthians 13:12. “For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known.” This line floats in to the discussion but is never explicitly addressed, instead Oshii uses reflections throughout the film to show Kusanagi’s inward gaze. She confronts her reflection in many ways, maybe the most profound is during a commute across the city where she encounters an identical cyborg “twin” working in a high rise. “You’re treated like other humans, so stop with the angst,” her partner tells her. “That’s the only thing that makes me feel human: the way I’m treated,” Kusanagi replies. To know and be fully known is the great, overarching quest of humanity. We know in part, Paul writes to the Corinthian church, but when the perfect comes the partial knowledge will be replaced by complete knowledge. Our “true selves” are as image bearers of God, created to represent God in a constructed world. The Major feels her “ghost” but knows via direct experience that she can do things no human can. So what is she?

One conversation between Kusanagi and her teammate Batou references 1 Corinthians 13:12. “For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known.” This line floats in to the discussion but is never explicitly addressed, instead Oshii uses reflections throughout the film to show Kusanagi’s inward gaze. She confronts her reflection in many ways, maybe the most profound is during a commute across the city where she encounters an identical cyborg “twin” working in a high rise. “You’re treated like other humans, so stop with the angst,” her partner tells her. “That’s the only thing that makes me feel human: the way I’m treated,” Kusanagi replies. To know and be fully known is the great, overarching quest of humanity. We know in part, Paul writes to the Corinthian church, but when the perfect comes the partial knowledge will be replaced by complete knowledge. Our “true selves” are as image bearers of God, created to represent God in a constructed world. The Major feels her “ghost” but knows via direct experience that she can do things no human can. So what is she?

The question in the field of robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) of what constitutes “human” is one that ethicists and theologians have been asking since the advent of the digital age. “If AI is autonomous,” said one minister, “then we should encourage it to participate in Christ’s redemptive purposes in the world.” The concepts of “free will,” “consciousness,” and “soul” are already murkily defined for actual people, never mind virtual ones. Few theologians or philosophers agree on what any of it means (and none of those words are biblical so there’s not much help in direct appeals to “plainly reading the scriptures”). There’s already a growing movement of transhumanist religious adherents that wait for the singularity — the point in our history when we can upload our minds to a perfect virtual dimension and leave physicality behind. In this place, echoing Revelations, we will no longer have tears to wipe away and there will be no more death or suffering. The Turing Church even has a set of 10 Convictions that lays out a covenant with our future selves that we will do everything in our power to evolve past the burden of “legacy humanity.”

For fans of animation, Ghost in the Shell was a momentous achievement in design and narrative. Its influence on cyberpunk, science fiction, futurism, and pop culture continues to this day (literally, 2017 saw the release of the American remake starring Scarlett Johansson). The question of what makes us human and how we fit in to the universe are asked in fresh ways as our technologies threaten to make us obsolete, and the answer continues speaking in a still, small voice into our “ghosts” while we still have ears to hear.